Encouraging women into science

According to the Women in Science and Engineering (Wise) campaign’s latest analysis of UK labour market statistics, women make up just 23% of those in core science, technology, engineering or maths (STEM) jobs.

Plus, there are still considerably more boys studying science than girls – the latest Higher Education and Skills Agency (HESA) statistics showed that only 25% of graduates from UK universities with degrees in science are women.

This International Women’s Day – we are highlighting the incredible achievements of some of the most influential and inspiring women in STEM….

1. Helen Sharman-The first UK astronaut & first woman to visit the Mir Space Station!

Source – RocketSTEM

Helen Patricia Sharman is a British Chemist who became the first British astronaut and the first woman to visit the Mir Space Station in 1991!

Sharman was born in Grenoside, Sheffield on the 30th May 1963.

Project Juno

After responding to a radio advertisement asking for applicants to be astronauts for a mission to the Mir Space Station, Helen Sharman was selected for the mission live on ITV, on 25th of November 1989, ahead of nearly 13,000 other applicants.

Before launch, Sharman spent 18 months in intensive flight training in Star City.

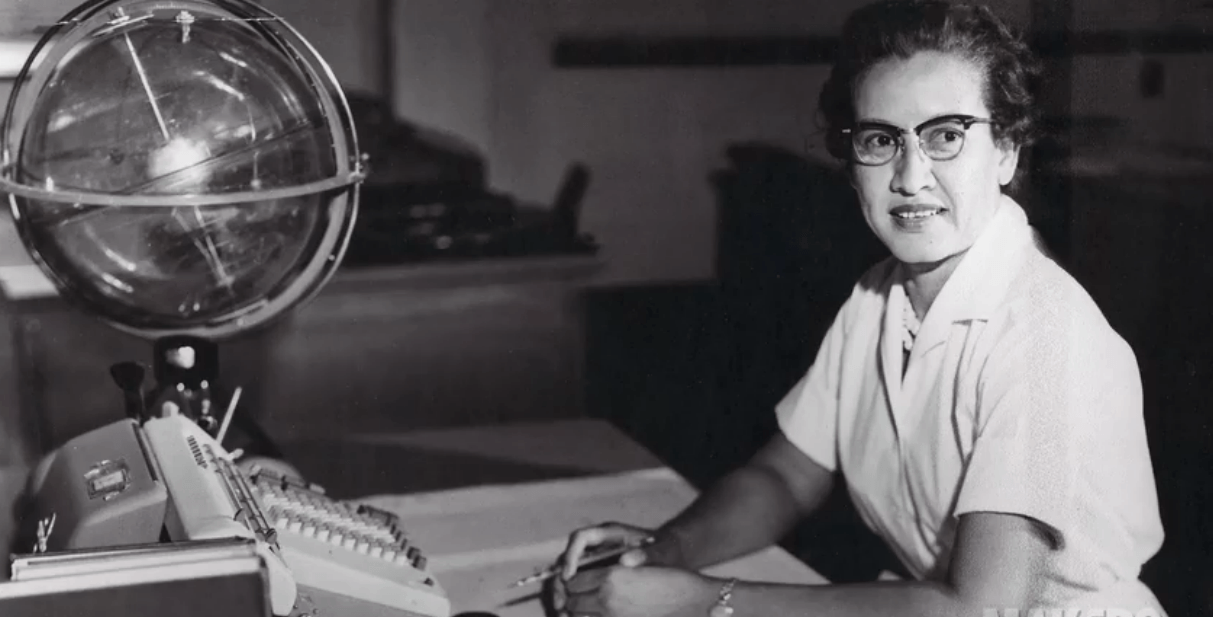

2. Katherine Johnson – Calculated the trajectory of the 1961 flight of Alan Shepard, the first American in space!

Source – NASA

Katherine Johnson is a former NASA mathematician.Born on August 26, 1918 in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, Johnson began her career in 1953 at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), the agency that preceded NASA, one of a number of African-American women hired to work as “computers” in what was then their Guidance and Navigation Department.

Career

Working at NASA Langley Research Center from 1953 until her retirement in 1986, Johnson made critical technical contributions which included, calculating the trajectory of the 1961 flight of Alan Shepard, the first American in space.

She also played a crucial role in verifying the calculations made by early electronic computers of John Glenn’s 1962 launch to orbit and the 1969 Apollo 11 trajectory to the moon.

Johnson worked on the Space Shuttle Program and the Earth Resources Satellite and encouraged students to pursue careers in STEM (science, technology engineering and mathematics).

3. Mary Jackson – NASA’S First Black Female Engineer! (1921 – 2005)

Source – NASA

After two years in the computing pool, Mary Jackson received an offer to work for engineer Kazimierz Czarnecki in the 4-foot by 4-foot Supersonic Pressure Tunnel, a 60,000 horsepower wind tunnel capable of blasting models with winds approaching twice the speed of sound. Czarnecki offered Mary hands-on experience conducting experiments in the facility, and eventually suggested that she enter a training program that would allow her to earn a promotion from mathematician to engineer. Trainees had to take graduate level math and physics in after-work courses managed by the University of Virginia. Because the classes were held at then-segregated Hampton High School, however, Mary needed special permission from the City of Hampton to join her white peers in the classroom. Never one to flinch in the face of a challenge, Mary completed the courses, earned the promotion, and in 1958 became NASA’s first black female engineer. That same year, she co-authored her first report, Effects of Nose Angle and Mach Number on Transition on Cones at Supersonic Speeds.

Mary Jackson began her engineering career in an era in which female engineers of any background were a rarity; in the 1950s, she very well may have been the only black female aeronautical engineer in the field.

4. Dorothy Vaughan – NASA’s first African-American manager! (1910 – 2008)

Source – NASA

It’s easy to overlook the people who paved the way for the agency’s current robust and diverse workforce and leadership. Those who speak of NASA’s pioneers rarely mention the name Dorothy Vaughan, but as the head of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA’s) segregated West Area Computing Unit from 1949 until 1958, Vaughan was both a respected mathematician and NASA’s first African-American manager.

Dorothy Vaughan came to the Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory in 1943, during the height of World War II, leaving her position as the math teacher at Robert Russa Moton High School in Farmville, VA to take what she believed would be a temporary war job. Two years after President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802 into law, prohibiting racial, religious and ethnic discrimination in the country’s defence industry, the Laboratory began hiring black women to meet the skyrocketing demand for processing aeronautical research data. Urgency and twenty-four hour shifts prevailed – as did Jim Crow laws which required newly-hired “coloured” mathematicians to work separately from their white female counterparts. Dorothy Vaughan was assigned to the segregated “West Area Computing” unit, an all-black group of female mathematicians, who were originally required to use separate dining and bathroom facilities. Over time, both individually and as a group, the West Computers distinguished themselves with contributions to virtually every area of research at Langley.

5. Libby Jackson – The Human Spaceflight and Microgravity Programme Manager for the UK Space Agency!

Libby Jackson is currently the Human Spaceflight and Microgravity Programme Manager for the UK Space Agency, so she is responsible for the UK’s Human Spaceflight and Microgravity programmes on the International Space Station (ISS).

She used to be a flight director on space missions, ensuring that everyone worked together and everything went according to plan.

Libby attended space school when she was 15, and that made her realise there was a space industry you could work in. Then in Year 12, she had to do a work placement and herself and a friend wrote to NASA – They never expected to get in, but to there amazement they were invited to do two weeks at the Johnson Space Center!

Libby has recently published a book –

A Galaxy of Her Own: Amazing Stories of Women in Space

From small steps to giant leaps, A Galaxy of Her Own tells fifty stories of inspirational women who have been fundamental to the story of humans in space, from scientists to astronauts to some surprising roles in between.

6. Valentina Tereshkova – First Woman in Space!

Source – Roscosmos

Interested in parachuting from a young age, Tereshkova began skydiving at a local flying club, making her first jump at the age of 22 in May 1959. At the time of her selection as a cosmonaut, she was working as a textile worker in a local factory.

After the first human spaceflight by Yuri Gagarin, the selection of female cosmonaut trainees was authorised by the Soviet government, with the aim of ensuring the first woman in space was a Soviet citizen.

On 16 February 1962, out of more than 400 applicants, five women were selected to join the cosmonaut corps: Tatyana Kuznetsova, Irina Solovyova, Zhanna Yorkina, Valentina Ponomaryova and Valentina Tereshkova. The group spent several months in training, which included weightless flights, isolation tests, centrifuge tests, 120 parachute jumps and pilot training in jet aircraft.

Four candidates passed the final examinations in November 1962, after which they were commissioned as lieutenants in the Soviet air force (meaning Tereshkova also became the first civilian to fly in space, since technically these were only honorary ranks).

Originally a joint mission was planned that would see two women launched on solo Vostok flights on consecutive days in March or April 1963. Tereshkova, Solovyova and Ponomaryova were the leading candidates. It was intended that Tereshkova would be launched first in Vostok 5, with Ponomaryova following her in Vostok 6.

However, this plan was changed in March 1963: Vostok 5 would carry a male cosmonaut, Valeri Bykovsky, flying the mission with a woman in Vostok 6 in June. The Russian space authorities nominated Tereshkova to make the joint flight.

Her daughter Elena, was the first child born to parents who had both been in space.

7. Sally Ride – First American Female Astronaut! (1951 – 2012)

Source – NASA

One of six women selected in NASA’s 1978 astronaut class, Sally Ride was the first of them to fly. When she rode aboard the space shuttle Challenger as it lifted off from Kennedy Space Center on June 18, 1983, she became the first American woman in space and captured the nation’s attention and imagination as a symbol of the ability of women to break barriers. As one of the three mission specialists on the STS-7 mission, she played a vital role in helping the crew deploy communications satellites, conduct experiments and make use of the first Shuttle Pallet Satellite. Her pioneering voyage and remarkable life helped, as President Barack Obama said soon after her death last summer, “inspire generations of young girls to reach for the stars” for she “showed us that there are no limits to what we can achieve.”

Fascinated by science from a young age, she pursued the study of physics, along with English, in school.

As she was graduating from Stanford University with a Ph.D. in physics, having done research in astrophysics and free electron laser physics, Ride noticed a newspaper ad for NASA astronauts. She turned in an application, along with 8,000 other people, and was one of only 35 chosen to join the astronaut corps. Joining NASA in 1978, she served as the ground-based capsule communicator, or capcom, for the second and third space shuttle missions (STS- 2 and STS-3) and helped with development of the space shuttle’s robotic arm.

.Retiring from NASA in 1987, she became a science fellow at the Center for International Security and Arms Control at Stanford University and, in 1989, joined the University of California-San Diego as a professor of physics and director of the California Space Institute. In 2001, she founded her own company, Sally Ride Science, to pursue her passion for motivating girls and boys to study the STEM fields-science, technology, engineering and math. The company creates innovative classroom materials, programs and professional development training for teachers.

In 2003 she also served on the presidential commission investigating the Columbia accident (the only person to serve on both commissions).

In addition to this work, she wrote a number of science books for children, including The Third Planet, which won the American Institute of Physics Children’s Science Writing Award in 1995.

In 2003, Ride was added to the Astronaut Hall of Fame. The Astronaut Hall of Fame honours astronauts for their hard work.

7. Roma Agrawal – A structural engineer on The Shard!

Source – IET

A structural engineer with a physics degree. She has always loved science and design and found engineering to be a great combination between the two.

She has designed bridges, skyscrapers and sculptures with signature architects over her ten year career. She spent six years working on The Shard, the tallest building in Western Europe, and designed the foundations and the ‘Spire’.

In addition to winning industry awards, her career has been extensively featured in the media, including on BBC World News, BBC Daily Politics, TEDx, The Evening Standard, The Sunday Times, Guardian, The Telegraph, Independent, Cosmopolitan and Stylist Magazines, documentaries and in online blogs. She was the only woman featured on Channel 4’s documentary on the Shard, ‘The Tallest Tower’. Roma was part of M&S’s ‘Leading Ladies’ campaign 2014 and was described as a top woman tweeter by the Guardian

Outside work, Roma promotes engineering, scientific and technical careers to young people and particularly to under-represented groups such as women. She also engages about these topics with the Institutions and government to understand and develop an effective way forward. Roma has spoken to over 3000 people at over 50 schools, universities and organisations across the country and organisations across the country and abroad!

Roma has recently released a book –

Built: The Hidden Stories Behind our Structures

A unique look at how construction has evolved from the mud huts of our ancestors to towers of steel that reach into the sky.

8. Ada Lovelace – The first ever computer programmer! (1815 – 1852)

Source – findingada.com

The idea that the 1840s saw the birth of computer science as we know it today may seem like a preposterous one, but long before the Bombe, the Colossus or the Harvard Mark I – long before any computer was actually built – came a remarkable woman whose understanding of computing remained unparalleled and unappreciated for 100 years. Brought up in an era when women were routinely denied education, she saw further into the future than any of her male counterparts, and her work influenced the thinking of one of World War II’s greatest minds.

Fearing that Ada would inherit her father’s volatile ‘poetic’ temperament, her mother raised her under a strict regimen of science, logic, and mathematics.

Ada herself from childhood had a fascination with machines – designing fanciful boats and steam flying machines, and poring over the diagrams of the new inventions of the Industrial Revolution that filled the scientific magazines of the time.

in 1833, Lovelace’s mentor, the scientist and polymath Mary Sommerville, introduced her to Charles Babbage, the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics who had already attained considerable celebrity for his visionary and perpetually unfinished plans for gigantic clockwork calculating machines. Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace both had somewhat unconventional personalities and became close and lifelong friends. Babbage described her as “that Enchantress who has thrown her magical spell around the most abstract of Sciences and has grasped it with a force which few masculine intellects could have exerted over it,” or an another occasion, as “The Enchantress of Numbers”.

In 1842 Lovelace translated a short article describing the Analytical Engine by the italian mathematician Luigi Menabrea, for publication in England. Babbage asked her to expand the article, “as she understood the machine so well”. The final article is over three times the length of the original and contains several early ‘computer programs,’ as well as strikingly prescient observations on the potential uses of the machine, including the manipulation of symbols and creation of music.

Although Babbage and his assistants had sketched out programs for his engine before, Lovelace’s are the most elaborate and complete, and the first to be published; so she is often referred to as “the first computer programmer”.

Babbage himself “spoke highly of her mathematical powers, and of her peculiar capability – higher he said than of any one he knew, to prepare the descriptions connected with his calculating machine.”

9. Maria Mitchell – The First Female Professional American Astronomer!

(1818 – 1889)

Source – Big Think Youtube

Maria Mitchell was an astronomer, librarian, naturalist, and above all an educator. She discovered a comet through a telescope, for which she was awarded a gold medal by the King of Denmark. She was then thrust into the international spotlight and became America’s first professional female astronomer.

Her father was a great influence on her life; Maria developed her love of astronomy from his instruction on surveying and navigation. At age 12, Maria helped her father calculate the position of their home by observing a solar eclipse. By 14, sailors trusted her to do vital navigational computations for their long whaling journeys. Maria pursued her love of learning as a young woman, becoming the Nantucket Atheneum’s first librarian.

She and her father continued to acquire astronomical equipment and conduct observations.

On October 1st, 1847, Maria was sweeping the sky from the roof of the Pacific National Bank on Main Street, where her father was the Cashier. She spotted a small blurry object that did not appear on her charts. She had discovered a comet!

After achieving her fame, Maria was widely sought after and went on to achieve many great things. She resigned her post at the Atheneum in 1856 to travel throughout the US and Europe. In 1865, she became Professor of Astronomy at the newly-founded Vassar College.

Maria was an inspiration to her students. It was Vassar College that Maria felt was truly her home. She believed in learning by doing, and in the capacity of women to achieve what their male counterparts could. “Miss Mitchell” was beloved by her students whom she taught until her retirement in 1888.

10. Dr Stacey Habergham-Mawson – the manager of the National School’s Observatory!

Source – LJMU

Stacey is the manager of the National School’s Observatory and science outreach officer at the Astrophysics Research Institute, Liverpool John Moores University.

Her work is specifically concentrated on the distribution of core-collapse supernovae in disturbed or merging galaxies.

She is very interested in the communication of physics, specifically astronomy, to the wider public. Stacey believes it is extremely important to share the work that goes on at university level with both the tax-payers who fund the majority of this work, and with a younger generation who may be inspired by the content.

Most of her work to date has been related to looking at the local environments of CCSNe in galaxies which are undergoing collisions or interactions with other galaxies, compared to those in “normal” systems.